So the latest thing I’ve tried baking are macarons. Not macaroons, the coconutty biscuit things, but the french almond meringue biscuits with fillings. The ones they fly into Brown Thomas from Laudaree in Paris daily and sell for obscene amounts of money. I figured, if I could make Madeline, why not something else classic and French? How hard could it be?

And the answer is, not very. They’re a little fiddly but ultimately if you can make a meringue and have some patience, macaron are just not as hard as everyone says they are.

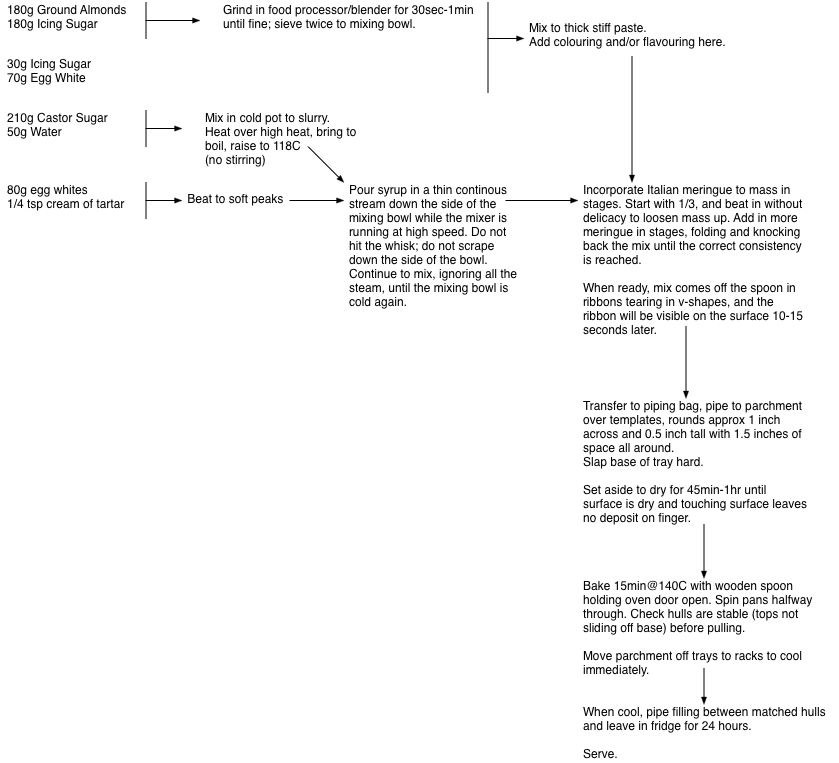

There are two or three things you have to do that don’t seem to be written in most of the books mind you, and if you skip those, you get awful results. So here’s my recipe, with notes:

This makes enough macaron biscuit mix to fill one standard large disposable piping bag and that can make up to sixty macaron (120 hulls) if you make them small. I don’t suggest making them small, the less mass in a macaron hull, the fiddlier the timing on the bake.

180g ground almond

180g icing sugar

Place in a food processor or blender and run it for about 40 seconds. Tip the resulting flour into a large bowl, making sure to get all the bits that will have caked to the sides of the food processor bowl. Now take another large bowl and a sieve, and sieve the contents of the first bowl into the second. Some of the contents won’t sieve, it’ll look like cornmeal or polenta grains. There shouldn’t be much of this, but you might have a few spoons on this first pass. Discard it into the bin. Now sieve the contents of the second bowl back to the first bowl. And repeat this process, discarding anything that doesn’t make it through the sieve, at least twice.

This is the first thing that tripped me up. The thing is, almonds, like all nuts, have oil in them; grind them fine and you get a paste, not a flour – you have to add powdered sugar to the mix to stop that, or have fancy equipment or techniques like cryomilling (which I can’t do because liquid nitrogen’s not readily available here). So most companies selling ground almonds don’t grind them fine. And if you just use their stuff neat, you get a macaron that looks like you made it out of sand and worse yet, it won’t hold liquid properly so it won’t bake right. Either take the time to do this grind-and-sieve routine (and if you discard a lot of material, you’ll have to start off with a lot more; you want 360g of mixture when you finish, not when you start ideally) … or else go to one of the fancy online shops and buy the mix pre-ground and pre-made. It’s not cheap, but neither are ground almonds. I pay about €15 per kilo of ground almond (in the Asia Food Co on Mary St. in Dublin) – Meilleur du Chef will charge you €20 per kilo of the final mix, plus shipping. Your call.

Either way, with the mix made, put it in a bowl (one of the two you used will be fine) and add 30g of icing sugar and 70g of egg white.

The egg whites are a bit of a thing with macarons, especially if you use the french meringue method (I tried that method, it was too fiddly and slow). If you’re getting them by cracking and separating eggs, you’re advised to let them sit in the fridge for a few days to age, so the proteins break down and they don’t form as firm of a meringue which makes making the final mix easier. Personally, I just buy a bottle of egg whites from Dunnes and don’t bother to get the freshest one on the shelf. I mean, you want to leave a petri dish for bugs in your fridge for a week, well hey, it’s your immune system. Me and my aged pasteurised egg white in a convenient container will be over here.

Now take a wooden spoon because silicone spatula heads tend to come off the handles in mixes this stiff, and fold all the liquid into all the powder. It’ll take a minute, but there is enough powder to do it.

A note here – if you’re adding colours or flavours to the hull, you can do so here. Just mix the powdered flavour (like espresso grounds or finely ground tea leaves or matcha tea); or powdered food colourings or even gel food colourings, into the mix at this point. Liquid food colourings and essences are trickier because even that little liquid here can be a bit of a pain. I stick to powders and gels for colourings if I use them and powders for flavour.

A related note is that you can use any nut to make a macaron, it doesn’t have to be almond. Almond’s nicely neutral, so if you want to use pistachios, say, you can just swap out a portion of the almonds instead of all of them. Experiment. I tend to use 2/3 pistachio when making pistachio macarons. I’ve tried using breadcrumbs for bread flavour with limited success too.

Step 2:

Next up, take 80g of egg white and put it in the bowl of your stand mixer. You can do this with a handheld electric whisk in an ordinary bowl but a stand mixer is more convenient. If you have neither of these, don’t make macaron. You’d badly injure yourself trying to do this with a hand whisk.

Add a half-teaspoon of cream of tartar to the egg whites. You could skip this, it’s designed to help the meringue form, but that’d just be masochistic.

Whip the eggs to soft peaks and then stop whisking completely. You don’t want too much air in here. You can add some liquid flavours here if you want – vanilla, various essences, that kind of thing.

Step 3:

Here’s where you can get some serious scarring so don’t be stupid.

Take 210g of castor sugar and put it in a pan. Preferably a medium sized one with a pouring spout, but it’s not mandatory. Don’t put it in a small pan though because any boilover would be a pain in the fundament. Add 50g of water to make a slurry, and stir the dry sugar into the water with an ordinary spoon. You just want all the dry sugar made wet, it won’t dissolve yet. Throw the spoon in the sink now; you won’t be stirring this again. Put the pan on full heat and leave it come up to 118C. Don’t stir. Swirl if you have to in order to ensure it’s melting evenly at the beginning, but generally this is a don’t-touch affair. Use a candy thermometer or an infrared thermometer (they’re nearly as cheap as a good candy thermometer these days – the gun ones are only about $30 on ebay and smaller pen ones go for as little as $15). Whatever you do, don’t stick a finger in there or splash it on yourself; at 118C, it’ll cook you if it hits you and it’s sticky when in contact with proteins (like, say, those found in human flesh). Generally bad news.

Once you get up to about 115C, it’s time for Step 4:

Turn the stand mixer up to full speed. When the sugar syrup hits 118C, carefully take the pan and pour the syrup down the side of the stand mixer’s bowl in a thin continous stream. Don’t dump it in all at once, but don’t add it drop by drop either, it’s cooling very rapidly now it’s off the heat and that thermal energy is needed in the mixer, not the air. Just pour in a thin, continuous, steady stream at the side of the bowl.

Don’t hit the mixer’s whisk. Don’t stop and scrape down the sides of the bowl. Just… pour.

Now let the mixer run until the steaming meringue mix in the bowl isn’t steaming any more and no longer looks like it wants to climb out of the bowl to strangle you. You can leave it continue to beat until the bowl goes cold; that’s the classical meringue technique. Or you can use it straight away. I can’t tell the difference really.

On to Step 5. And this one is a bit finicky. You have to mix the meringue into the mix from step 1. Which is a very stiff paste. But you don’t want to mix all of the meringue in. You will have a little left over at the end most of the time. You make a little more than you need because it’s a lot easier to have it and not need it than to need it and not have it.

Mix it in, a spatula load at a time. The first spatula or so, you can just beat in with the wooden spoon to loosen the paste up. No sense being delicate there, it won’t work. But the more you add, the looser it will get, so go easier as you go on. You do want to fold it in and keep some air; but not all of the air in the meringue is welcome; the macaron hulls are not light airy fluffy things, there’s a little density to them.

I don’t have an easy way to test for all this. You kindof have to do it by eye. I tend to pull the spatula from the mixture and let it drip in ribbons back onto the surface. If it can’t drip, it needs more meringue; but you want the ribbons to hold their shape on the surface of the mix for at least ten seconds. The consistency should be like overly thick potato soup, or thick porridge, and gauging it does just seem to be a try-it-and-see kind of thing.

Step 6:

Fill a piping bag with the mix; put a preprinted template (like this one) on a baking tray and put parchment paper over that, securing both with a small dab of the mix here and there. Now hold the piping bag vertically over the center of a circle on the template about 3mm off the parchment paper, and squeeze. Keep squeezing until the mix reaches the circle; then lift off vertically (you can snap if you know how, but a vertical lift, while leaving a tail, ensures you didn’t also leave a pit). Do that for all the circles in the template. Resist the urge to pipe over the template size; it never ends well. You need the gaps between the hulls as they will spread a little, and more importantly, they need to air-dry first.

Air-drying is really important for this process btw; once a tray’s piped, you have to leave it sit untouched for 40 minutes or more. Test it after that point by very gently pushing on a macaron. If the surface deforms and your finger stays dry, it’s ready to bake. If it sticks to your finger, it’s not. If you do this, when they go to expand in the oven, the skin that’s formed won’t split and the entire hull has to lift upwards, exposing new mix to the hot air of the oven which dries it even as the bubbles are exposed to the air; this becomes the foot, the little bubbly ridge around the base of each macaron hull.

Step 7:

Once airdried to a skin, set your oven for 150C and let it stabilise there, then put in the trays of macaron that have airdried, and close the oven door, but leave a wooden spoon in there to crack it so the water vapour can escape. Rotated the pans at 10 minutes, and cook for five more.

Step 8:

Remove the parchment and attached macarons to a rack and allow to cool.

Detach from the rack, match hulls for size and shape, then pipe filling and squeeze together.